Hoosier History Live is an independently produced new media project about Indiana history, integrating podcasts, website www.HoosierHistoryLive.org, weekly enewsletter, and social media. Its original content comes initially from a live with call in weekly talk radio show hosted by author and historian Nelson Price. You can hear the show live Saturdays from noon to 1 pm ET at WICR 88.7 fm or stream the show live at the WICR HD1 app on your phone, or at our website.

May 25, 2024

Alas, due to pre-emption by UIndy's WICR, there will be no live Hoosier History Live show on WICR this Sat. May 25. Look for "Birds of prey" with guest Mark Booth to air on June 1 at noon on WICR.

Do remember that our most valuable asset is our online product. The Hoosier History Live ARCHIVES is essentially our collection of previously aired shows that have been turned into podcasts, as well as their accompanying newsletters. And yes, we do control our online product! And yes, we do want you to share our enewsletters and podcasts!

And speaking of our ARCHIVES, here is a great show to listen to. Online, the modern way!

Speedway and medical care: the first 50 years

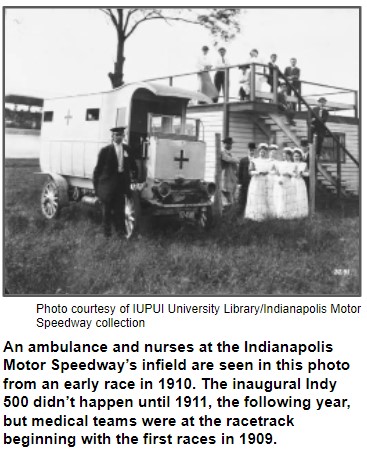

Doctors, nurses and ambulances have been part of the scene at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway since the first auto race in 1909, a disastrous, five-mile competition that resulted in the deaths of drivers, mechanics and spectators. (The inaugural Indianapolis 500 was not held until two years later, in 1911.) Medical, sports and social history began unfolding lickety-split at the world-famous racetrack. Hoosier History Live will explore the eras involving the Speedway's first three chief medical officers, a 50-year span ending in 1959.

Doctors, nurses and ambulances have been part of the scene at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway since the first auto race in 1909, a disastrous, five-mile competition that resulted in the deaths of drivers, mechanics and spectators. (The inaugural Indianapolis 500 was not held until two years later, in 1911.) Medical, sports and social history began unfolding lickety-split at the world-famous racetrack. Hoosier History Live will explore the eras involving the Speedway's first three chief medical officers, a 50-year span ending in 1959.

Helmets for Indy 500 drivers did not become mandatory until the mid-1930s. The first chief medical officer was overruled in 1914 when he disqualified a driver who had visual challenges. And the second chief medical officer resigned in 1951 when a beer tent was erected at the racetrack, saying he did not want to have to treat "drunks".

Those episodes and others will be explored during our show with Nelson's guest, medical historian Norma Erickson, the education manager at the Indiana Medical History Museum in Indianapolis. A long-time Indy 500 enthusiast, Norma has undertaken extensive research for "Speedway and Medicine" presentations at the museum in recent years.

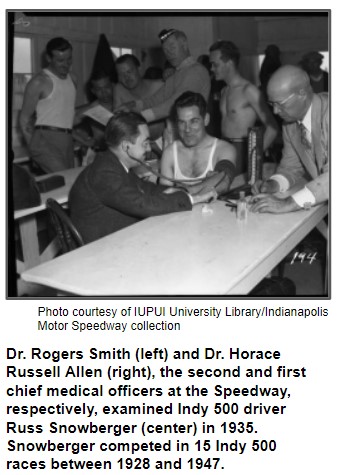

The Speedway's first chief medical officer, Dr. Horace Russell Allen (who served from 1909 to 1937), was, as might be expected, an orthopedic surgeon. But his two successors, Dr. Rogers Smith and Dr. C.B. Bohner, were, respectively, a neuropsychiatrist and an allergist. Although both assumed the top post after experience on the medical staff during races, qualifications and practices in May.

In 1958, Dr. Bohner oversaw about 250 medical workers, eight First Aid stations, 12 ambulances and an infield hospital with 25 physicians, 36 nurses and a dentist, according to Norma's research. Although Dr. Bohner's stint as chief medical officer from 1952-1959 involved several horrific accidents, Norma notes that substantial safety improvements also occurred. Flame-proof clothing, often dipped in boric acid, became standard, "or at least more accepted" for drivers and crew members at the racetrack.

By the 1930s, Dr. Allen had lobbied for drivers to wear abdominal protectors. Before that, Indy 500 race driver and World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker (who later owned the Speedway) recalled that, for protection, drivers had often wrapped themselves in cloths, almost like mummies, underneath their uniforms.

By the 1930s, Dr. Allen had lobbied for drivers to wear abdominal protectors. Before that, Indy 500 race driver and World War I flying ace Eddie Rickenbacker (who later owned the Speedway) recalled that, for protection, drivers had often wrapped themselves in cloths, almost like mummies, underneath their uniforms.

The chief medical officer's advice and decisions didn't always prevail, according to Norma's research. In 1914, Dr. Allen rejected driver Ray Gilhooly because his vision was weak, but the physician was overruled.

Dr. Allen prevailed in 1933, though, when he disqualified popular driver Howdy Wilcox II because of his diabetes, then a disorder that could not easily be controlled. In 2011, driver Charlie Kimball became the first driver to compete in the Indy 500 with Type 1 diabetes; Speedway officials explained the criteria had not changed, but that Kimball was appropriately managing his diabetes.

The casualties at the 1909 sprint race were the result of the track's surface, initially a mix of crushed rock and tar. The surface broke apart, causing the deaths of two drivers, two mechanics and two spectators. After that, the surface was replaced with paving bricks.

From the beginning, the intense heat has posed challenges for drivers and spectators. According to Norma's research, three-time Indy 500 winner Wilbur Shaw noted that, before donning his helmet, he often stuck it in a refrigerator. He used the same refrigerator that cooled the bottle of milk given to the winning driver.

Your contributions help keep Hoosier History Live on the air, on the web, in your inbox, and in our ARCHIVES!

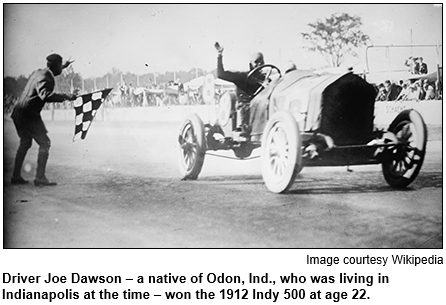

After 22-year-old native Hoosier

After 22-year-old native Hoosier  Speaking of vintage: Many Hoosiers know a bit about

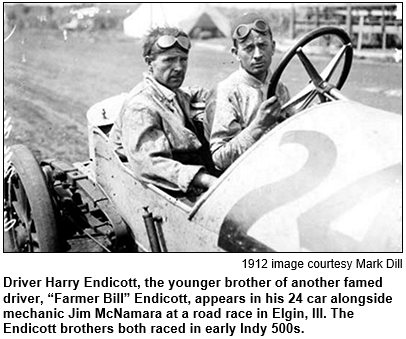

Speaking of vintage: Many Hoosiers know a bit about  Other early Indy 500s drivers we will explore include

Other early Indy 500s drivers we will explore include  Barney Oldfield, who even starred in a Broadway musical, generally is considered to have been the first American auto racing celebrity. According to the website of the

Barney Oldfield, who even starred in a Broadway musical, generally is considered to have been the first American auto racing celebrity. According to the website of the